Research

Prospects for Seismology by a Uranus Flagship Orbiter

Ring seismology has delivered valuable constraints for Saturn’s interior that have yet to be fully understood. Would similar science be possible from a new mission to orbit Uranus?

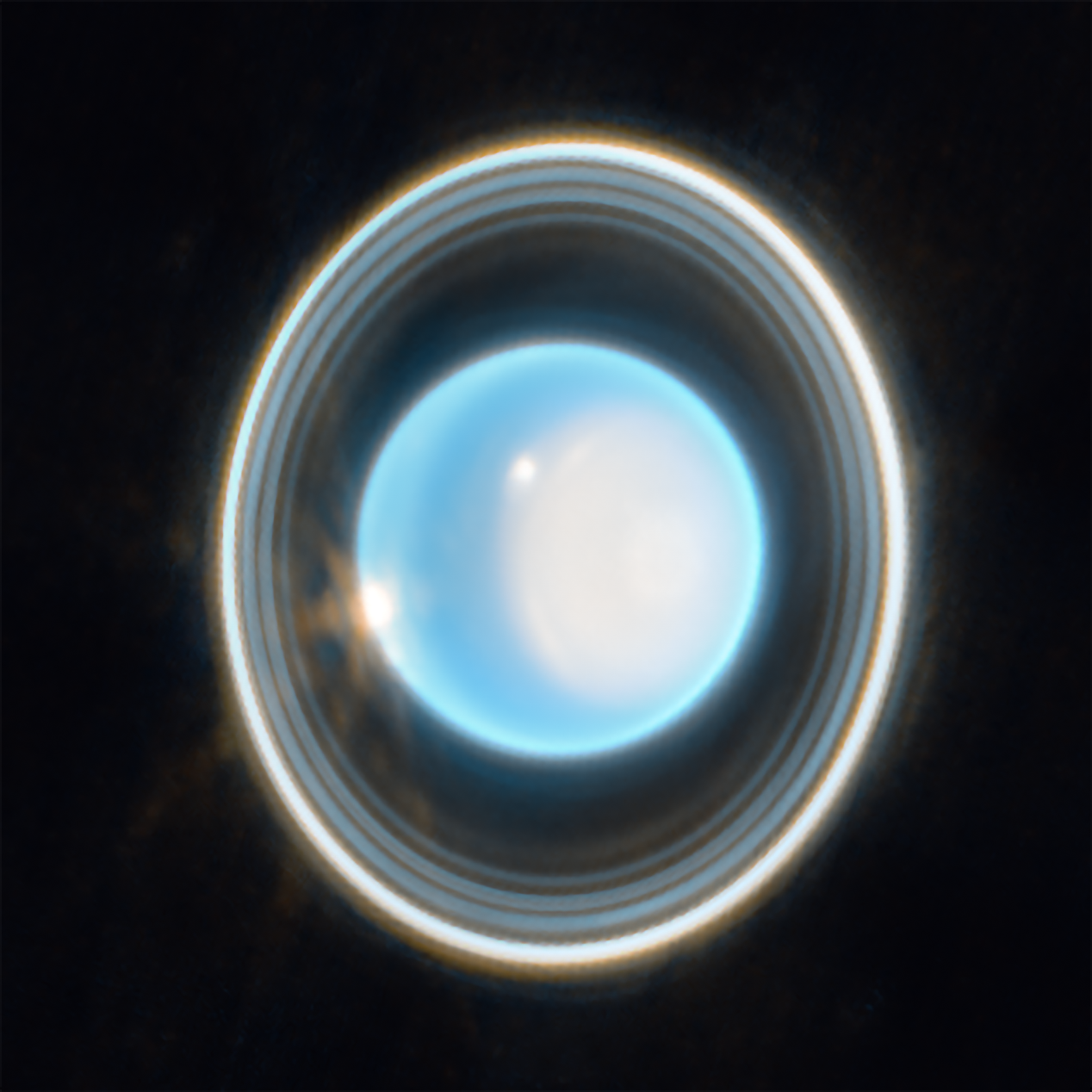

Uranus has 13 named rings, 10 of which are dense and narrow, some spanning just 2 km wide. The fact that Uranus’s ring system is mostly empty space means that resonances between ring orbits and the planet’s internal oscillations might be more rare than at in Saturn’s broad rings. However, such narrow rings are liable to spread over time due to viscosity, suggesting that some external forcing has been at work sculpting these narrow rings. Shepherd moons explain the confinement of the epsilon ring, but the confinement mechanism is elusive for the 6, 5, 4, alpha, beta, eta, gamma, delta, and lambda rings. Could it be gravitational forcing by Uranus’s internal oscillations? Notably, many more faint unnamed rings are visible in images obtained as Voyager 2 looked back at Uranus after its flyby, and these too might be a good place to search for signatures of resonant forcing by the planet’s internal oscillations. (JWST image credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI)

Uranus has 13 named rings, 10 of which are dense and narrow, some spanning just 2 km wide. The fact that Uranus’s ring system is mostly empty space means that resonances between ring orbits and the planet’s internal oscillations might be more rare than at in Saturn’s broad rings. However, such narrow rings are liable to spread over time due to viscosity, suggesting that some external forcing has been at work sculpting these narrow rings. Shepherd moons explain the confinement of the epsilon ring, but the confinement mechanism is elusive for the 6, 5, 4, alpha, beta, eta, gamma, delta, and lambda rings. Could it be gravitational forcing by Uranus’s internal oscillations? Notably, many more faint unnamed rings are visible in images obtained as Voyager 2 looked back at Uranus after its flyby, and these too might be a good place to search for signatures of resonant forcing by the planet’s internal oscillations. (JWST image credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI)

To find out, we would search for wave-like signatures on ring edges or midpoints or logitudinal brightness variations in ring imaging from Voyager or JWST. A Uranus orbiter would be uniquely situated to search for signals of Uranus’s oscillations in the rings, up close and personal, with modest hardware: at its basic level this science could be achievable with a camera with resolution similar to Voyager’s narrow-angle camera.

A higher-risk, potentially higher-reward strategy for measuring Uranus’s oscillation spectrum would be to fly an orbiter with a Doppler imager dedicated to planetary seismology. Such an instrument makes maps of the velocity of a planet’s rumbling atmosphere, which can be analyzed to extract frequencies and amplitudes of the subtle oscillations. Instruments like this have been deployed on the ground and trained on the Sun, Jupiter, and Saturn (see here and here) and would present a unique opportunity to detect acoustic oscillations (sound waves) in a giant planet interior for the first time. Since this higher-frequency category of oscillations does not register in the rings, this kind of dedicated instrumentation offers the best means of their detection.

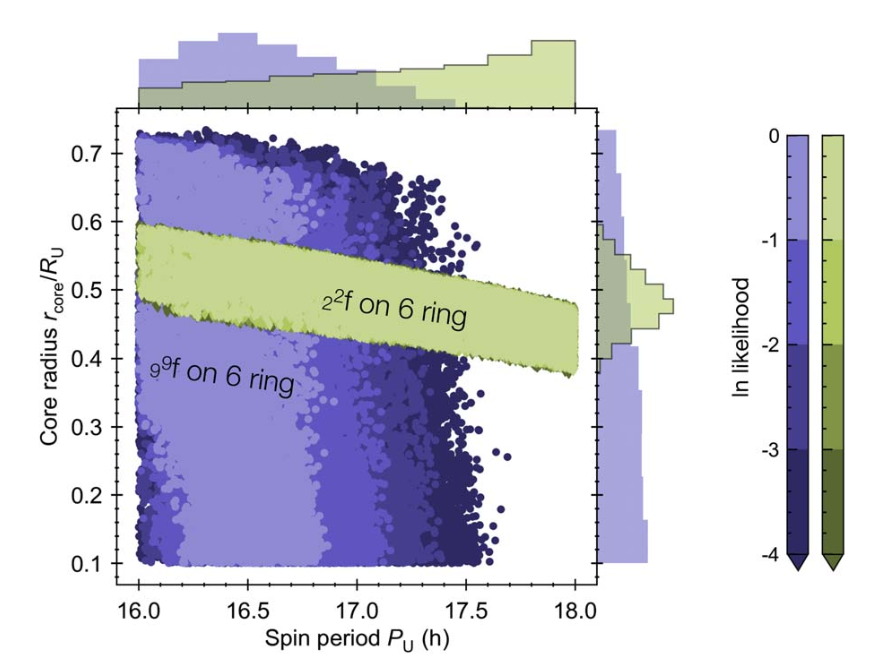

Our paper published in PSJ considers what we know about Uranus’s interior structure today, and uses models to show how much we might learn if a Uranus orbiter delivers any new detections of Uranus oscillation modes through the rings or a Doppler imager. What we would learn depends on exactly what we get, but the findings are encouraging: if ring seismology delivers the frequency of an oscillation mode that involves the deep interior of the planet, this can rule out a large fraction of the interior structures in currently in contention for Uranus. If a more superficial oscillation mode is detected, we expect new information about Uranus’s internal rotation state that can be used to independently test the rotation period implied by observations of Uranus’s magnetosphere. The acoustic mode spectrum delivered by a Doppler imager would be more uniquely constraining for Uranus’s internal structure, but Doppler imaging requires a lot of continuous observation time, and so the feasibility of this type of observation depends strongly on what orbit is required by the mission’s other science objectives.

Uranus Gravity Science: Diving through the rings?

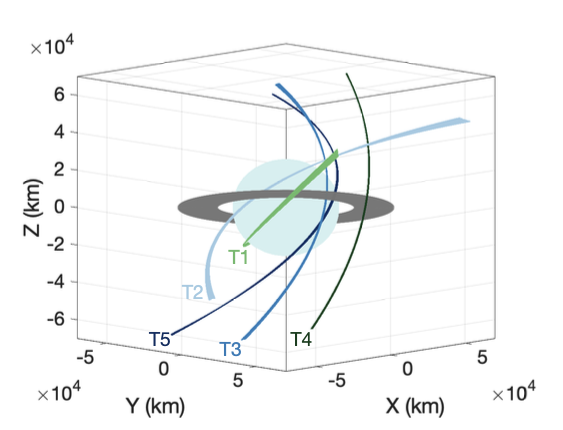

Designing the trajectory for a mission like the Uranus Orbiter and Probe is an art, balancing a huge range of disparate observations that are all required to serve the mission’s science objectives. To better understand Uranus’s interior, we scientists need information about the planet’s gravitational and magnetic fields, which contain some of the most direct information about the planet’s internal composition and core structure, heat flow, and turbulent dynamics. From far away, these fields appear smooth and featureless, but up close, an abundance of rich structure is revealed. In the gravity field, these smaller spatial scales contain vital clues about the depth to which the giant planets’ atmospheric zonal flows penetrate. The strong zonal wind patterns turn out to penetrate thousands of kilometers deep in Jupiter and Saturn, discoveries that would not have been possible with Juno and Cassini’s highly eccentric and inclined orbits that made it possible to fly within thousands of km of the planets’ cloud tops.

Our PSJ paper published in November 2025 considers a number of candidate trajectories and evaluates the precision with which each one would measure Uranus’s gravity field. By applying these expected measurements to a large set of Uranus interior models, we find that the unknown depth of Uranus’s zonal winds acts as a confounding variable that makes it difficult to draw any definitive conclusions about Uranus’s interior structure. However, if an orbiter can fly between Uranus’s atmosphere and the innermost (zeta) ring, we expect enough sensitivity to detect or rule out deep winds, resolving what would otherwise be a degenerate interpretation for Uranus’s internal structure. The uncertain conditions interior to the dusty zeta ring will need to be studied in more detail to judge the risk posed to the spacecraft.

Sounding Saturn’s Interior using Ring Seismology

The interior structure of the giant planets are traditionally constrained by their gravity fields, which NASA’s Juno and Cassini missions measured to exquisite precision for Jupiter and Saturn respectively. Analysis of those data have already revealed Jupiter’s interior in unprecedented detail, and similar work is underway for Saturn.

The interior structure of the giant planets are traditionally constrained by their gravity fields, which NASA’s Juno and Cassini missions measured to exquisite precision for Jupiter and Saturn respectively. Analysis of those data have already revealed Jupiter’s interior in unprecedented detail, and similar work is underway for Saturn.

A very different dataset obtained by Cassini observations of Saturn’s rings is proving to challenge our understanding of Saturn’s interior as well. It has been known since the time of the Voyagers that the rings are studded with waves driven by resonant forcing by Saturn’s moons, but Cassini observations have made it possible to identify a subset of these waves that are driven by resonances with the free oscillations of Saturn itself. The precise determination of the frequencies and number of spiral arms that Cassini scientists have been able to achieve for each of these roughly 20 waves associated with Saturn oscillations has generated an extremely well-resolved power spectrum, making it possible to do seismology of a giant planet for the first time. For some thorough discussion and background, see this excellent blog post from Emily Lakdawalla at The Planetary Society.

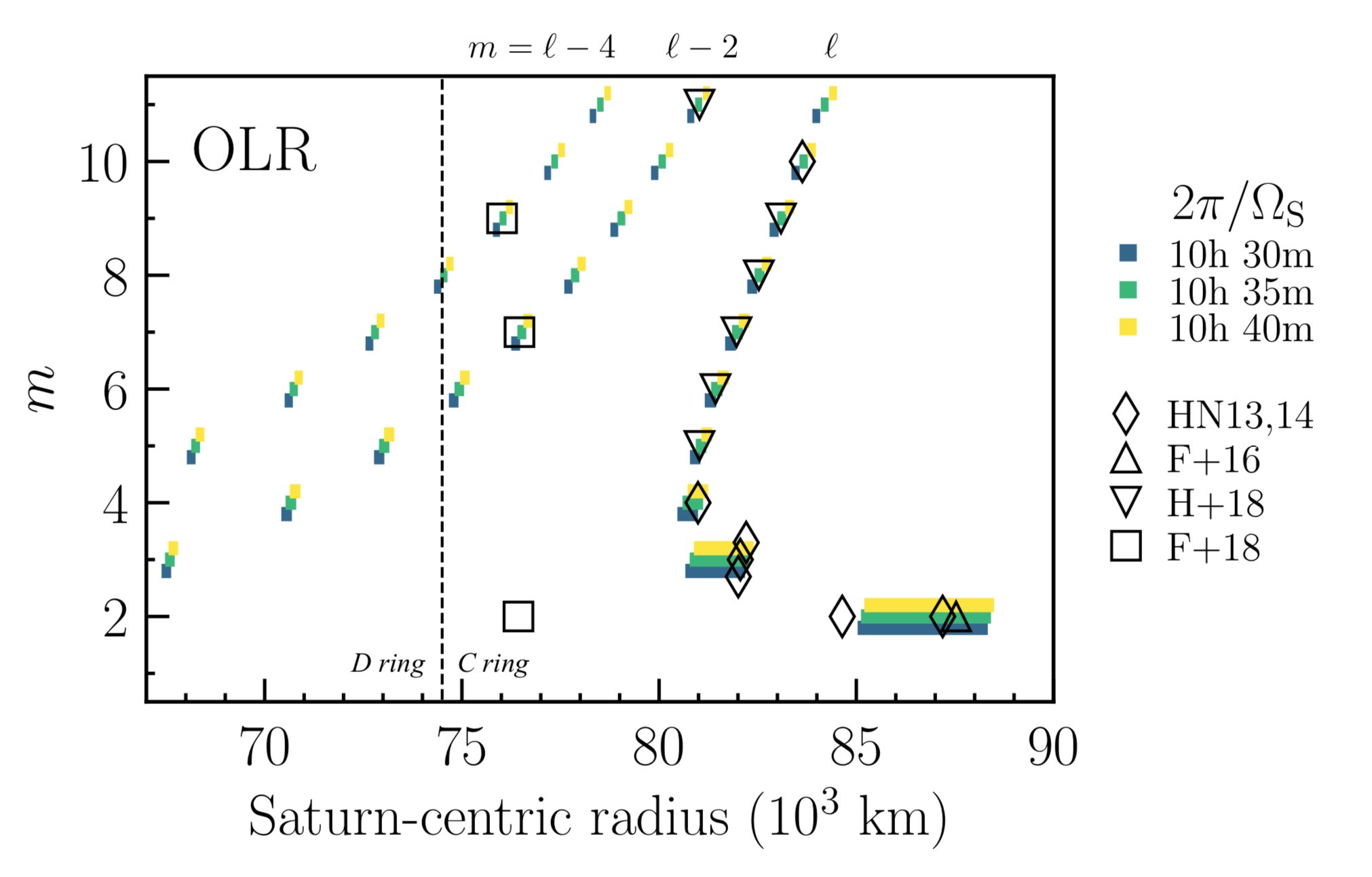

This figure from our 2019 paper compares the locations of Lindblad (horizontal) resonances that we expect for Saturn’s fundamental tones given our interior models (green/yellow bars) to the observed locations of spiral density waves that propagate toward Saturn (open symbols), the signature of waves caused by perturbations inside the rings. We used our Saturn models to confirm that Saturn’s fundamental tones are the origin of the vast majority of these waves. Then we leveraged the fact that these frequencies are modulated by Saturn’s rotation to measure Saturn’s bulk rotation rate, a quantity which has been notoriously tough to determine through other means. Later, Janosz Dewberry developed improved computational techniques for treating a planet’s rapid and differential rotation when solving for oscillation modes, leading to our updated work on Saturn’s rotation from ring seismology.

Another part of Saturn’s mode spectrum glimpsed in the rings is even more interesting. The two- and three-armed spiral waves that Saturn stirs up in the rings tell a story of a more complicated spectrum, one in which the fundamental modes are coupling to some other type of mode that was only hinted at as a possibility in the foundational work on this topic. Jim Fuller hypothesized that the fundamental (f) modes were mixing with internal gravity (g) modes, implying that part of Saturn’s deep interior is not convective. Ring seismology is unique in its ability to shed light on the fluid stability deep within a giant planet. In my time at Caltech, Jim and I collaborated to show that the Cassini gravity and ring seismology data suggest that Saturn’s interior hosts a stably stratified heavy element gradient, which may be a relic of the accretion process during Saturn’s formation.

Helium rain in Jupiter and Saturn

The mesmerizing flows in the atmospheres of the gas giants are well known, but beneath the surface things get even stranger. Whereas the plasma in the interior of the Sun can be understood to a fair approximation as an ideal gas, Jupiter and Saturn are cold and dense enough that the matter in their deep interiors takes the form of fluid metallic hydrogen, a highly conductive and yet free-flowing material believed to be the medium for the generation of Jupiter and Saturn’s strong magnetic fields.

There is a curious phenomenon predicted to accompany the transition from ordinary molecular hydrogen to fluid metallic hydrogen at around a million times atmospheric pressure: the phase separation of helium, the second most abundant constituent of these planets and the universe at large. Much like cloud or fog formation in our own atmosphere is driven by the condensation of water vapor in air cooled below its dew point, a fraction of the helium mixed into the liquid metallic hydrogen deep in a gas giant tends to separate from the mixture. If the microscopic pockets of helium-rich material manage to grow large enough (around a millimeter in size) by atomic diffusion, then helium-rich droplets can rain out of the otherwise well-mixed medium.

This figure is a simulation of how the helium distribution inside Saturn may have evolved over the history of the solar system. The initially uniform mixture of hydrogen and helium accreted from the protosolar nebula eventually differentiates as a result of the planet’s incessant cooling driven by its contraction. We think this helium rain is a significant power source for Saturn, where well-mixed models have historically failed to predict Saturn’s large observed intrinsic luminosity. In our 2016 paper we built similar models for helium rain in the evolution of Jupiter. From these simulations we estimated the degree to which helium rain inhibits convection in favor of double-diffusive convection, and derived constraints on the hydrogen-helium phase diagram such that the helium depletion from Jupiter’s surface is consistent with the 1998 in situ measurement by the Galileo Entry Probe.

This figure is a simulation of how the helium distribution inside Saturn may have evolved over the history of the solar system. The initially uniform mixture of hydrogen and helium accreted from the protosolar nebula eventually differentiates as a result of the planet’s incessant cooling driven by its contraction. We think this helium rain is a significant power source for Saturn, where well-mixed models have historically failed to predict Saturn’s large observed intrinsic luminosity. In our 2016 paper we built similar models for helium rain in the evolution of Jupiter. From these simulations we estimated the degree to which helium rain inhibits convection in favor of double-diffusive convection, and derived constraints on the hydrogen-helium phase diagram such that the helium depletion from Jupiter’s surface is consistent with the 1998 in situ measurement by the Galileo Entry Probe.

Trapping of mixed modes as a clock for red clump stars

A star the mass of the Sun will eventually exhaust the hydrogen available for nuclear fusion at its center, reorganizing itself into a red giant that will spend of order a hundred million years fusing hydrogen in a shell. Once this fusion has produced a degenerate, nearly pure helium core of sufficient mass to trigger fusion of helium by the triple-alpha process, the star will undergo helium core flashes before settling into quiescent core helium burning as a red clump star.

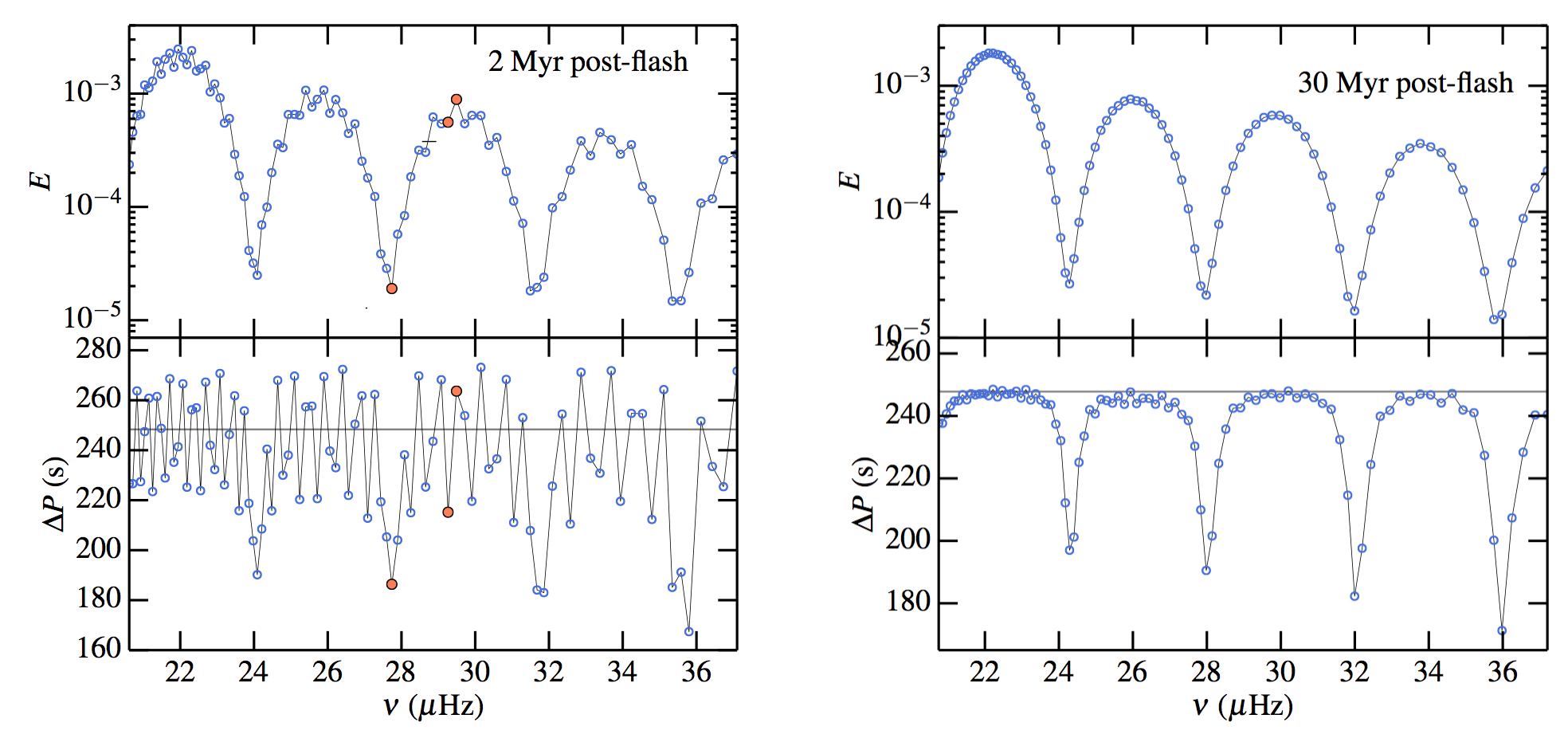

Red giants generally support mixed modes, in which acoustic overtone (p-)modes with high amplitudes in the star’s convective envelope tend to undergo degenerate mixing with internal gravity (g-)modes occupying the star’s stably stratified helium core. For a star that undergoes the helium core flash, the high-gravity degenerate core present at the onset of the helium core flash produces an abrupt abundance transition from nearly pure helium to the protostellar hydrogen-helium mixture. This transition produces a formidable feature in the Brunt-Väisälä frequency, tending to trap g-modes on one side or another of the transition. The frequencies of the g-modes are accordingly changed, producing a quite complicated spectrum of mixed modes observable by the Kepler or CoRoT spacecraft.

The figure here shows the complexity of the spectrum of dipole (l=1) mixed modes at early times on the red clump, where g-dominated mixed modes (those with the highest mode inertia E) deviate dramatically from the asymptotic expectation for the g-mode period spacing of ~250 s. Over some tens of millions of years, the combination of atomic diffusion at the density interface and the reestablishment of hydrogen shell fusion act to erode this steep barrier to g-mode propagation, relaxing the period spacings of g-dominated mixed modes back to the asymptotic prediction. The variance in period spacings observed for stars like these can thus differentiate between young and evolved clump stars, in spite of their having similar luminosities, surface gravities, and effective temperatures.